Gene-edited pig kidney now functions well in human body

It continues to function well after 32 days of transplat in a man declared dead by neurologic criteria: New York University Langone Transplant Institute

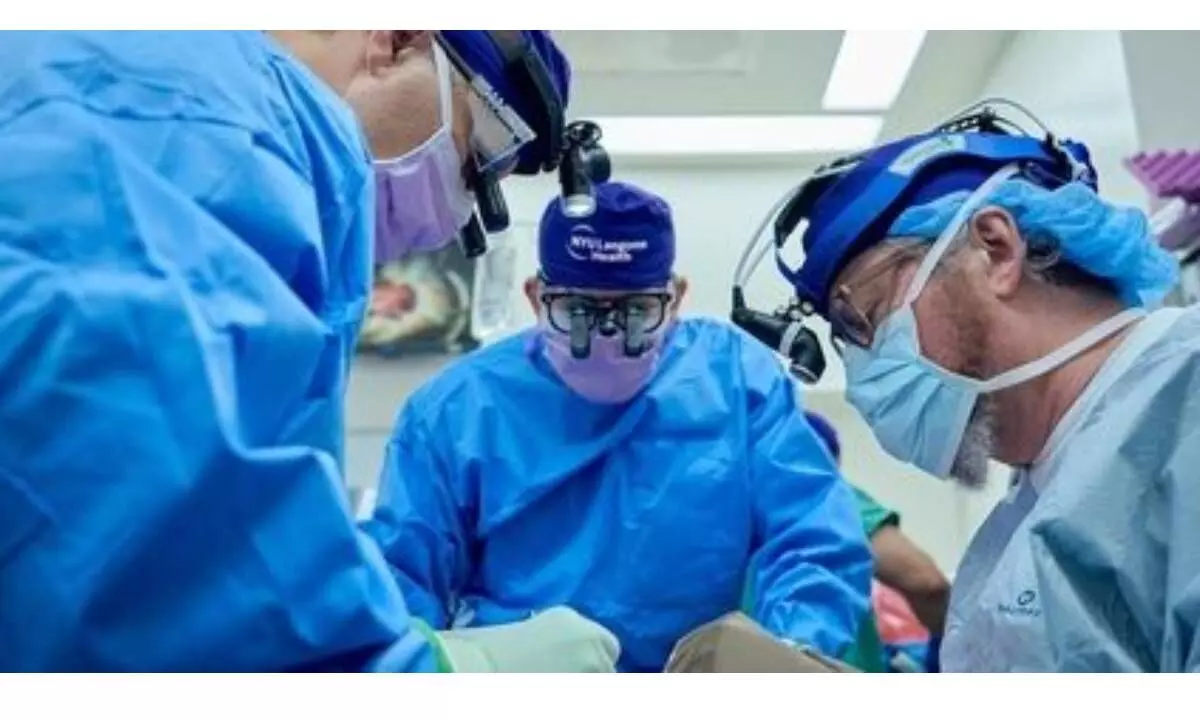

image for illustrative purpose

New York In a ray of hope for thousands of kidney transplant patients, surgeons at New York University Langone Transplant Institute have transplanted a genetically engineered pig kidney that continues to function well after 32 days in a man declared dead by neurologic criteria and maintained with a beating heart on ventilator support.

This represents the longest period that a gene-edited pig kidney has functioned in a human, and the latest step toward the advent of an alternate, sustainable supply of organs for transplant.

The procedure, performed on July 14, and led by Robert Montgomery, chair of the Department of Surgery, and director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute, was the fifth xenotransplant performed at NYU Langone.

Observation is ongoing, and the study will continue through mid-September 2023, the university said in a statement.

"This work demonstrates a pig kidney - with only one genetic modification and without experimental medications or devices - can replace the function of a human kidney for at least 32 days without being rejected," said Dr Montgomery.

He had previously performed the world's first genetically modified pig kidney transplant into a human decedent on September 25, 2021, followed by a second similar procedure on November 22, 2021.

Surgeons with the Transplant Institute performed two genetically engineered pig heart transplants in summer 2022.

The first hurdle to overcome in xenotransplants is preventing so-called hyperacute rejection, which typically occurs just minutes after an animal organ is connected to the human circulatory system.

By "knocking out" the gene that encodes the biomolecule known as alpha-gal -- which has been identified as responsible for a rapid antibody-mediated rejection of pig organs by humans -- immediate rejection has been avoided in all five xenotransplants at NYU Langone.

To ensure the body’s kidney function was sustained solely by the pig kidney, both of the transplant recipient’s native kidneys were surgically removed.

One pig kidney was then transplanted and started producing urine immediately without any signs of hyperacute rejection, said the university.